So we're on our way to Volubilis, through a beautiful countryside.

So we're on our way to Volubilis, through a beautiful countryside.Volubilis

So we're on our way to Volubilis, through a beautiful countryside.

So we're on our way to Volubilis, through a beautiful countryside.

Seen here are examples of the "greeness" of Morocco. Everywhere we look, even in the more hilly and mountainous areas, there is still green fields and agriculture.

Here are some pictures of a feature that caught my eye. As I've seen irrigation ditches in nearly every country, I've never seen these elevated irrigation "tubes", for lack of a better description. They are from maybe two feet off the ground , up to perhaps six feet high. They are uncovered, and few by pump stations.

Older irrigation tubes are found adjacent to other fields

Acres and acres of beautiful fields

Here a field of artichokes

More newly built apartments

Both occupied and newly built living quarters

The only train station I saw

Government buildings

Towns scattered across and surrounded by fields

And we start seeing more sheep and shepherds

The flat fields give way to hills

Farms surrounded by hay fields and more artichokes fields

Notice, if you can, the ox pulling the plough

The field of olive trees protected by a cactus fence

A cactus fence, olive trees and artichokes

An olive tree orchard

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

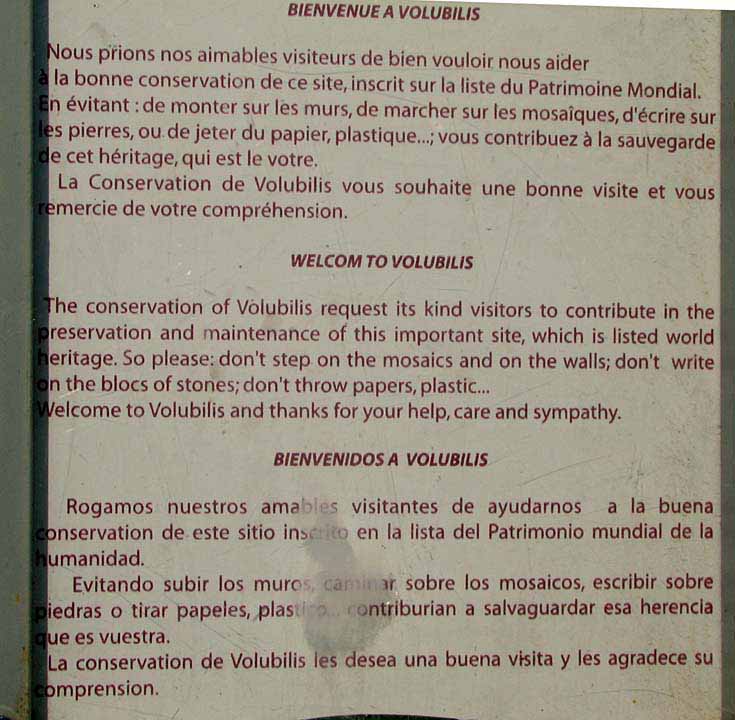

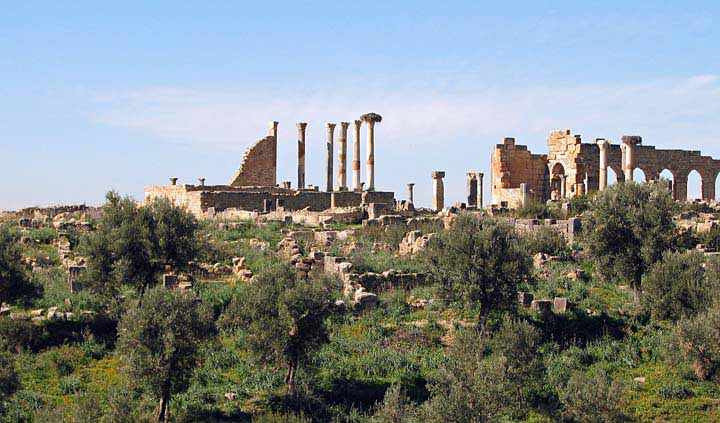

And we come upon Volubilis, a World Heritage Site

one of the largest ancient ruins in Africa

Volubilis

(Arabic: Walili) is an archaeological site in Morocco situated

near Meknes between Fez and Rabat. Volubilis features the best-preserved Roman

ruins in this part of northern Africa. In 1997 the site was listed as a UNESCO

World Heritage site

In antiquity, Volubilis was an important Roman town situated near the westernmost border of Roman conquests. It was built on the site of a previous Carthaginian settlement from (at the latest) the third century BC. Volubilis was the administrative center of the province in Roman Africa called Mauretania Tingitana.

The Romans evacuated most of Morocco at the end of the 3rd century AD but, unlike some other Roman cities, Volubilis was not abandoned. However, it appears to have been destroyed by an earthquake in the late fourth century AD. It was reoccupied in the sixth century, when a small group of tombstones written in Latin shows the existence of a community that still dated its foundation by the year of the Roman province.

Volubilis'

structures were damaged by the 1755 Lisbon earthquake; while in the 18th century

part of the marble was taken for construction in nearby Meknes.

In

1915, archaeological excavation was begun there by the French and it continued

through into the 1920s. Extensive remains of the Roman town have been uncovered.

From 2000 excavations carried out by revealed what should probably be

interpreted as the headquarters of Idris I just below the walls of the Roman

town to the west. Excavations within the walls also revealed a section of the

early medieval town

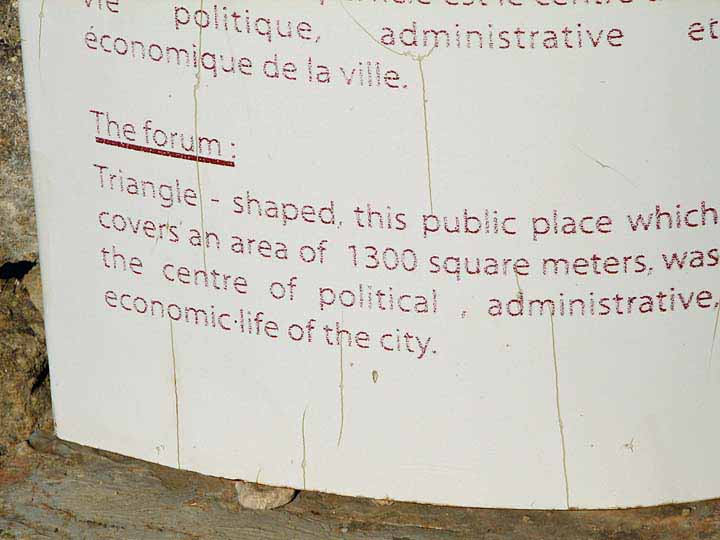

The forum

Yes, here the pelicans nest

We look down to a small village nearby

It seems that virtually everywhere we've visited, regardless of the country, we find Roman ruins. In some places, as in Turkey, the ruins are as fine, if not finer, than any we've seen in Italy. Here, again, are Roman ruins. Unfortunately, where other country's Roman sites have not withstood the test of time, the strength of earthquakes, the theft of materials for building other sites, or theft of antiquities by museums, theses ruins cannot withstand lack of care.

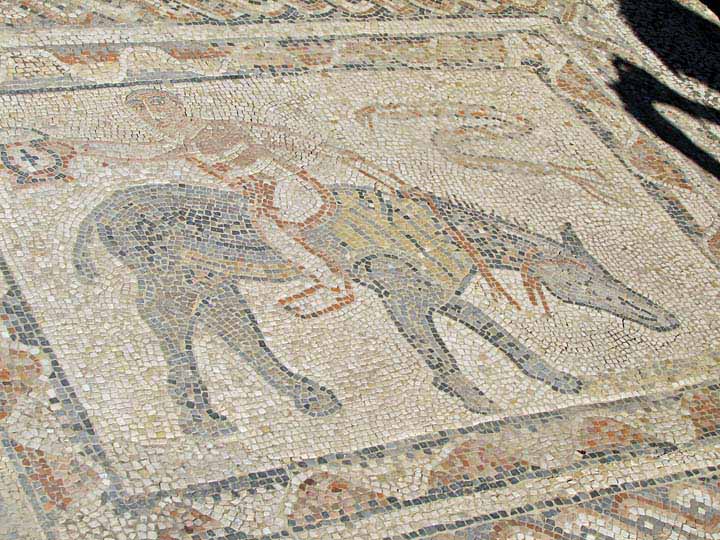

While sites filled with local wild flowers and greens are attractive, here they are simply overgrown. Sites with mosaics are more often protected by screens, or are carefully maintained, the mosaics found here are exposed, often covered by mud, and appear to have been picked over by visitor/thieves.

One visitor's guide calls Volubilis the "neglected jewel" - amen!

However, having said that, there is an aura of past grandeur and a pulse of history - people who walked these paths, lived in these buildings, wandered the cities, enjoyed the baths, lived and died without ever leaving the immediate area. This remains true of Volubilis.

The forum

No, not all visitors are foreign tourists; we share the site with small groups of those who appear to be Moroccans.

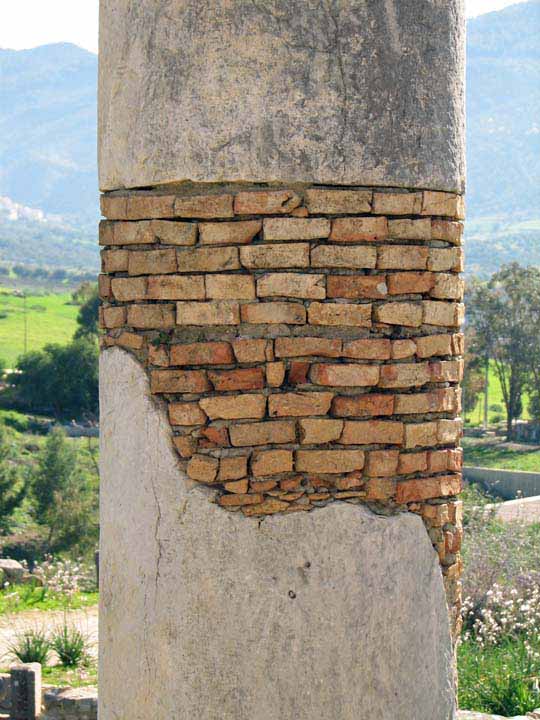

Some of the earlier repairs and reconstructions were done in an unusual , but artistic manner.

Other locations appear to remain only rubble.

But the beauty of the location cannot be denied.

An old grain mill

Views of the surrounding countryside

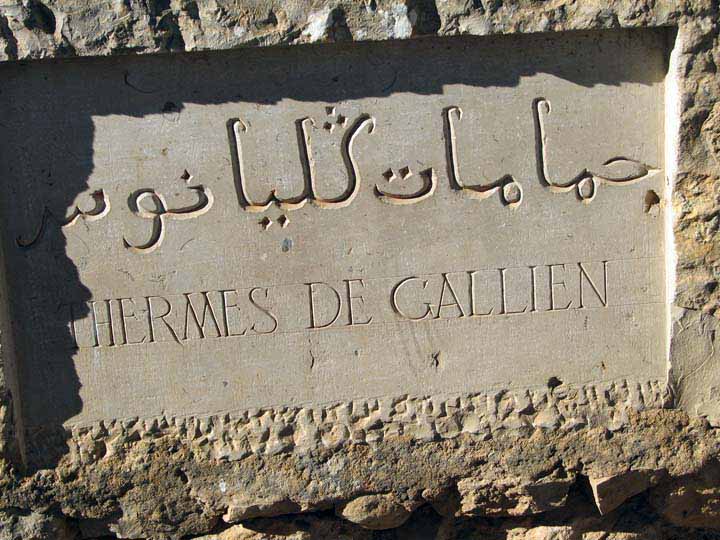

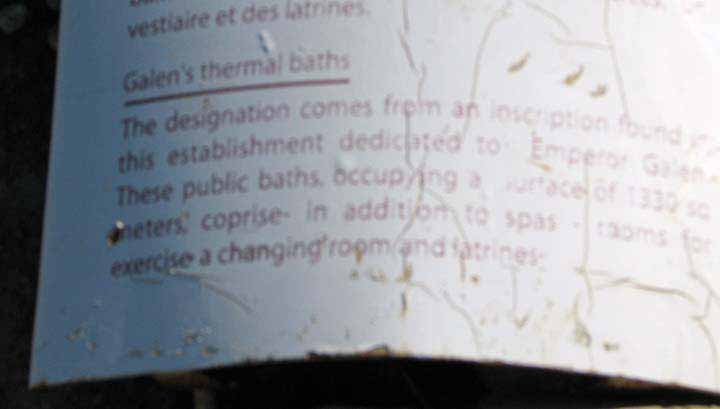

Gallien Baths - the first of many baths we saw

The city had extensive storm drains and sanitation

There is some repair and renovation occurring, but as you see, this is work being done more as labor than scientific efforts.

The Orphet House

Here we start to see our first mosaics and underground structures

Sometimes the mosaics are broken or separated

Heating area for heating water for the baths

And we see the first of many baths - with ornate mosaics and finely carved stone furnishings

Notice the real and imaginary sea creatures

A forest and wild animals

Elephants

As we leave this home, we are again exposed to the beautifully green fields

A basin to wash feet prior to gaining the bath

Many of the mosaics are missing and very faded - also covered by a layer of dust and mud

This is a deep bath with benches carved into the walls for relaxing

Some of the arches and walkways between homes

An ancient grinding stone

In the distance, above the homes, the forum stands

carved stone lays asunder

There are thermal baths in Volubilis

Stone walkways provided the town with foot traffic

There are many example of stone work

There are many example of stone work

A drain provides a colorful picture

The Forum

Our group of "legislators" fill the Forum steps

The Forum has a large government area

We enter another area with outstanding, if neglected, mosaics

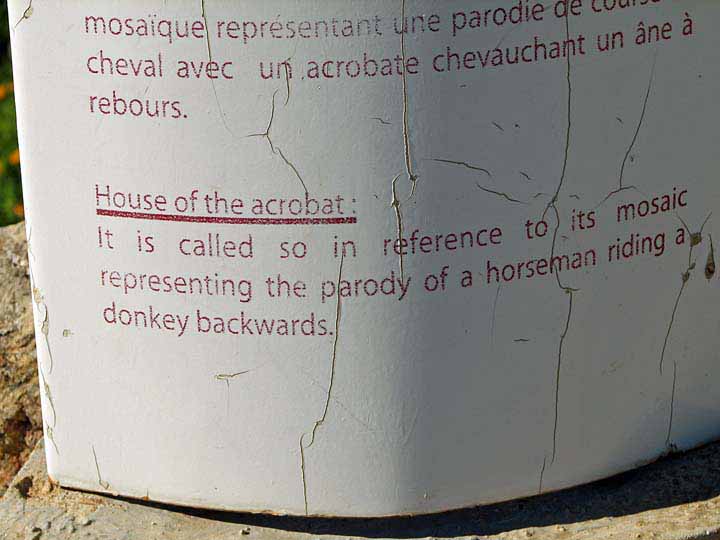

The House of the Acrobat

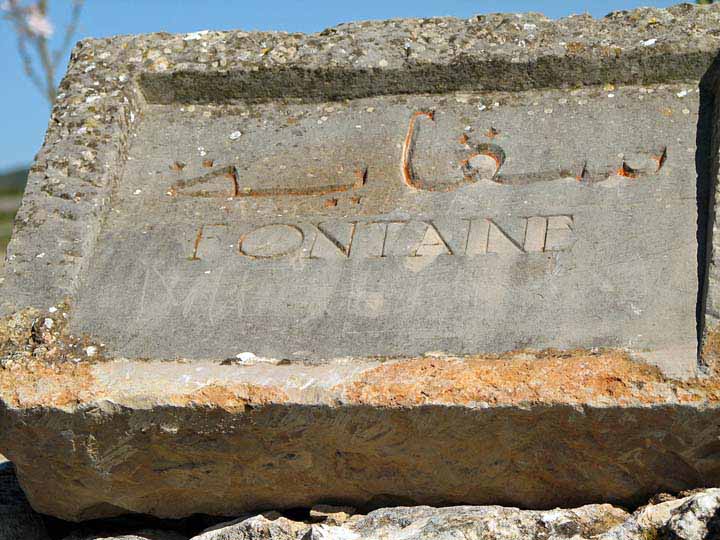

The Fountain

These mosaics represent swimmers and sea creatures

Elaborate spillways provide for water movement

Arch of Caracalla

I've included a number of picture of the Caracalla Arch because of its majesty

and the details that remain - both portraits and inscriptions

The square

Street from a city gate

Walking the town

Impressive doors to homes

Impressive doors to homes

Doors between rooms

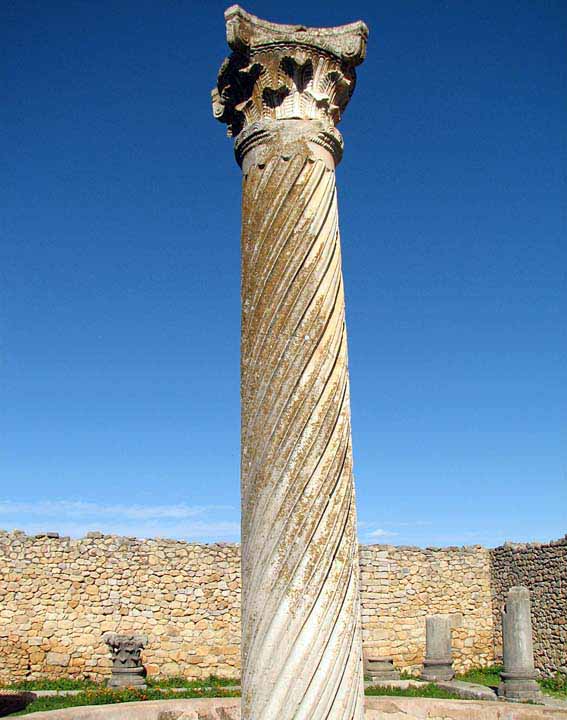

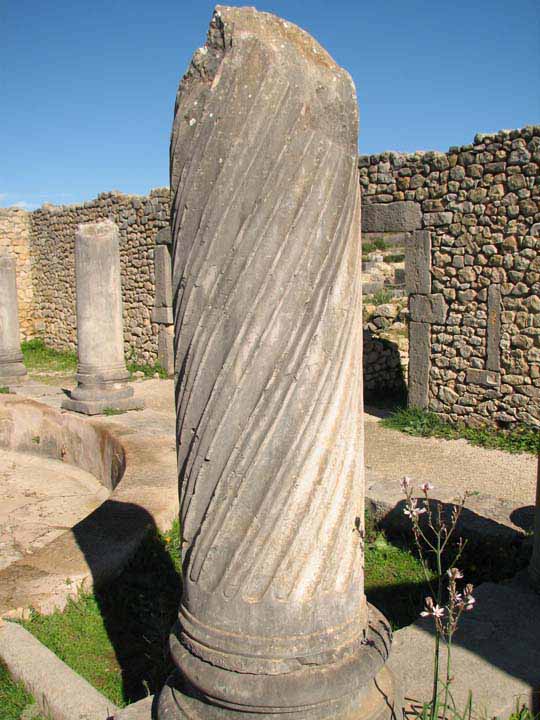

Beautiful columns

Notice some doorways were on guides

A central pool

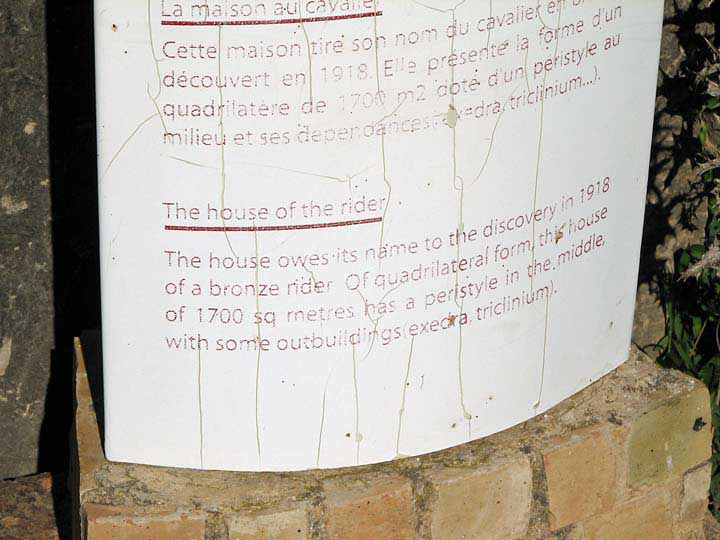

The house of the Jumper

Rails used during earlier excavations

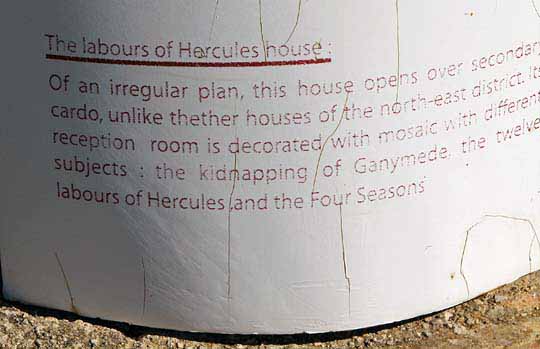

The House of the Labors of Hercules

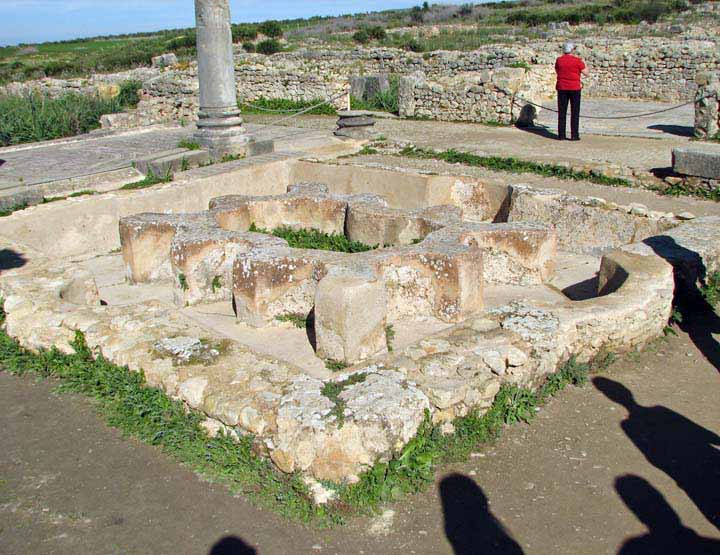

A central bath with seating in the middle as well as the sides

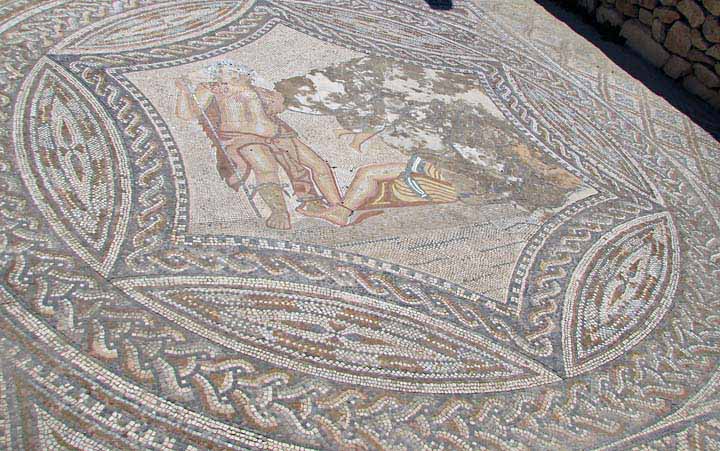

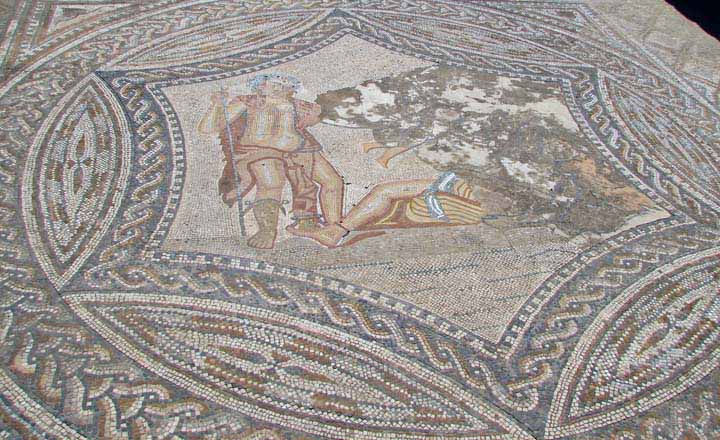

Some of the patterned mosaics of this famous home

In the center of the main mosaic - Hercules

He is surrounded by many of his famous deeds - his "labors"

In another home

A fountain with mosaic corners

We cross the main street to another section

The Triumphal Arch

As we start our walk our, we catch views of the larger area

As usual, I'm attracted by the wild flowers blooming everywhere

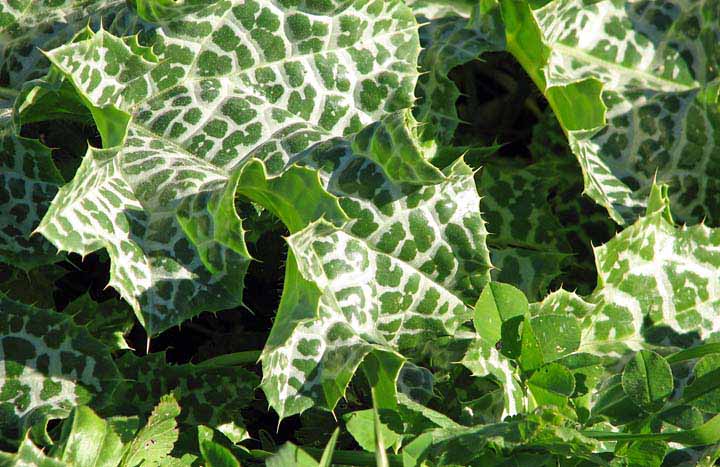

Here we see an unusual vine. At first we thought it had a dusting of a type of mold or disease

Upon closer examination the veins contrast with the color of the leaves

The Basilica

With this last view, we leave

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

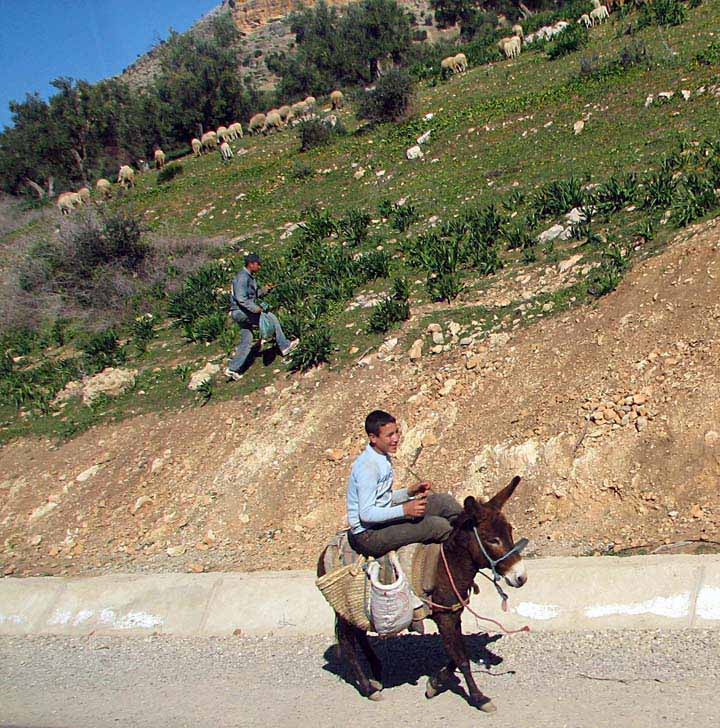

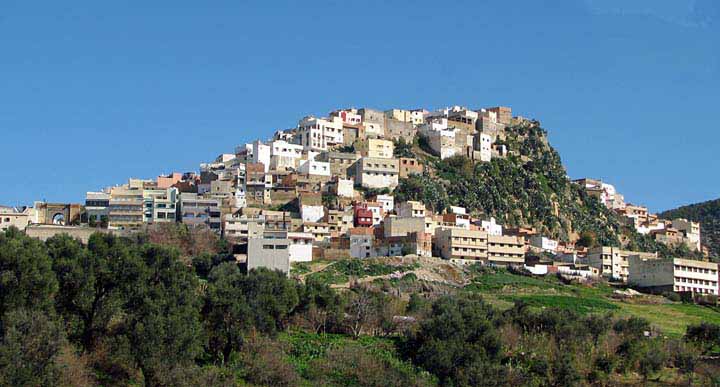

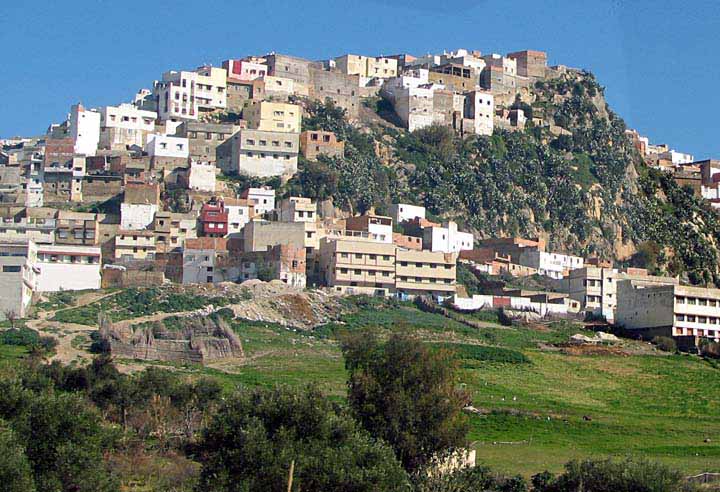

So we're on the way to Meknes. There's some more of the picturesque countryside; this time we see more hilly, rocky land.

We see more sheep and agricultural practices - donkey transportation

One

small town we pass has their old grinding wheel at the entrance to the town

Sacred

sites of Morocco and Islamic pilgrimage from Northwest Africa

Islam was brought to North Africa by early Arab warriors conquering territories and by traders voyaging back and forth along ancient trans-Saharan caravan routes. The first African pilgrimages to Mecca were from Cairo during the era of the Fatamid dynasties (909-1171). These early Muslims, traveling in camel caravans across the Sinai Peninsula to the Hijaz region of Arabia (where Mecca is located), established a route that was used continuously until the 20th century.

By the 13th century, pilgrim routes across

North Africa from as far west as Morocco linked with the Cairo caravan to Mecca.

Three caravans were regularly started from the Moroccan towns of Fez, Marrakech

and Sijilmasa. They often combined on the route and proceeded under a united

leadership eastward across the North African deserts. Composed of pilgrims,

merchants and guards, the great caravans often had a thousand or more camels.

Covering perhaps twenty miles a day and visiting the fabled Islamic mosques of

Tlemcen (Algeria) and Kairouan (Tunisia), they took many months to reach Egypt.

Scattered throughout the deserts, coastlines

and mountains of Morocco are sacred sites and pilgrimage places specific to the

indigenous Berber culture and the Roman, Jewish and Islamic people who settled

in the northwest reaches of the African continent.

In 788 (or 787) AD, an event occurred that

was to forever change the trajectory of Moroccan culture. Idris ibn Abdallah (or

Moulay Idris I as he is called in Morocco), the great-grandson of the Prophet

Muhammad fled west from Baghdad and settled in Morocco. The heir to the Umayyad

Caliphate in Damascus, Moulay had participated in a revolt against the Abbasid

dynasty (which had usurped the leadership of the Umayyad dynasty and

precipitated the split between the Shia and Sunni sects). Forced to flee Abbasid

assassins soon thereafter tried to establish himself among the remnants of the

old Roman city of Volubilis. Before long he moved to the nearby region of

Zerhoun, where he founded the town that is now called either Moulay Idris or

Zerhoun, and which is the most venerated pilgrimage site in all of Morocco.

Moulay Idriss

The Mausoleum of Moulay Idriss is one of the most spectacular devotionals of more than six hundred religious pilgrimages to saintly shrines in Morocco.

In 788, a

descendant of the Prophet Mohammed, named Moulay Idriss, was proclaimed king by

the Berber tribes. Moulay Idriss quickly became powerful and influential but was

murdered by a rival. The village which is the location of his tomb is now called

Moulay Iddriss and is one of the most sacred shrines in Morocco. The son Moulay Idriss, Moulay Idriss II took over and founded the present city

of Fez, the capital at that time.

Throughout

the centuries the mausoleums (burial sites) of Moulay Idris I in Zerhoun and

Moulay Idris II in Fez have become the primary pilgrimage sites in Morocco.

Originally it was thought that Idris II was buried, like his father, in Zerhoun,

but the discovery in 1308 of an uncorrupted body in Fez, gave impetus to the

establishment of a cult of Moulay Idris II. Local women who come to light

candles and incense, and pray for ease in childbirth venerate the cult's shrine.

The Sultan Moulay Ismail rebuilt the shrine itself in the 17th century.

The existence of pilgrimage places, other than the holy shrine of the Ka'ba in Mecca, is a controversial subject in Islam. Orthodox Muslims, following the dictates of Muhammad's revelations in the Koran, will state that there can be no other pilgrimage site than Mecca. Likewise, Orthodoxy maintains that the belief in saints is not Koranic. The reality, however, is that saints and pilgrimage places are extremely popular throughout the Islamic world, particularly in Morocco, Tunisia, Iraq and Shi'ite Iran.

A

typically Moroccan phenomenon is maraboutism. A marabout is either a saint or

his tomb. The saint may be a figure of historical importance in Moroccan culture

(such as Moulay Idris I) or a Sufi mystic of sufficient piety or presence to

attract a following. Dozens of saints from ages past are still revered by

Moroccans, and their musims, or feast days are the occasion for the assembling

of large crowds at the za'wiya of the saint. Besides their religious functions,

Musims feature horse races, folk dancing, song recitals and colorful markets

filled with native crafts. The two most important musims are those of Moulay

Idris the elder in Zerhoun on August 17 and Moulay Idris the younger in Fez in

mid-September.

Besides the mausoleums of Moroccan saints, certain mosques also attract large numbers of pilgrims. Primary among these are the Kairouine mosque of Fez and the Kutubiya (Koutoubia) mosque of Marrakech.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

I tried to get pictures of Moulay Idris, but as we were moving on the bus, I wasn't very successful. The pictures I did take follow - sorry to disappoint. The town is built on a fairly steep hill, and from the highway, you get a glimpse between trees and such

Alas I got no picture showing the shrine. As it is considered the most holy in Morocco , I did steal a picture from another website. The site is called Amazighroots, the page is labeled

Sacred Sites of Morocco, and the URL is - http://amazighroots.blogspot.com/2007/05/sacred-sites-of-morocco.html

I appreciate them sharing this picture of the green roofed holy site on the Internet.

This picture is not apropos of anything in particular, other than these reeds are used very often to build fences around gardens, homes and other properties. This was the only clear (almost Clear) shot I got the entire trip.

Meknes

(Berber:

Meknas or Ameknas, French: Meknès,

Spanish: Mequinez) is a city in northern Morocco. Meknes

was the capital of Morocco under the reign of Moulay Ismail (1672–1727),

before it was relocated to Marrakesh. The population is 985,000 (2010 census).

It is the capital of the Meknes-Tafilalet region. Meknes is named after a Berber

tribe.

The original community from

which Meknes can be traced was an 8th century Kasbah. A Berber tribe called the

Miknasa settled there in the 9th century, and a town consequently grew around

the previous borough.

The Almoravids founded a fortress here in the 9th century. It resisted to the Almohads rise, and was thus destroyed by them, only to be rebuilt in larger size with mosques and large fortifications. Under the Merinids it received further Maadrasas, kasbahs and mosques in the early 14th century, and continued to thrive under the Wattasid dynasty. Meknes saw its golden age as the imperial capital of Moulay Ismail following his accession to the Sultanate of Morocco (1672-1727). He installed under the old city a large prison to house Christian sailors captured on the sea, and also constructed numerous edifices, gardens, monumental gates, mosques (whence the city's nickname of "City of the Hundred Minarets") and the large line of wall, having a length of 40 km.